By: Jeff Collins for the Orange County Register

Almost half of the state’s municipalities are vulnerable to a little-known provision that has created a virtual zoning holiday.

Despite local objections, high-rise apartment buildings could soon spring from low-rise neighborhoods across Southern California.

To the horror of slow-growth proponents and neighborhood preservationists, proposals range from a six-story apartment building in suburban Orange to 2,000 units in a 1.9-million-square-foot, 20-level complex in Santa Monica.

But because these cities didn’t have a state-approved housing plan when developers filed their applications, local leaders can’t use zoning rules or their general plans to stop them.

A little-known provision called the “builder’s remedy” created a virtual zoning holiday for developments that include low-income housing, even though the proposals, according to one city council member, are “out of scale for the community.”

“These projects, by and large, are in places where we don’t have mid-rise to high-rise buildings now,” said Santa Monica Councilmember Phil Brock. “This is the question I think every city is having. How do you do what the state’s telling us to do?”

Cities across California are now grappling with that question.

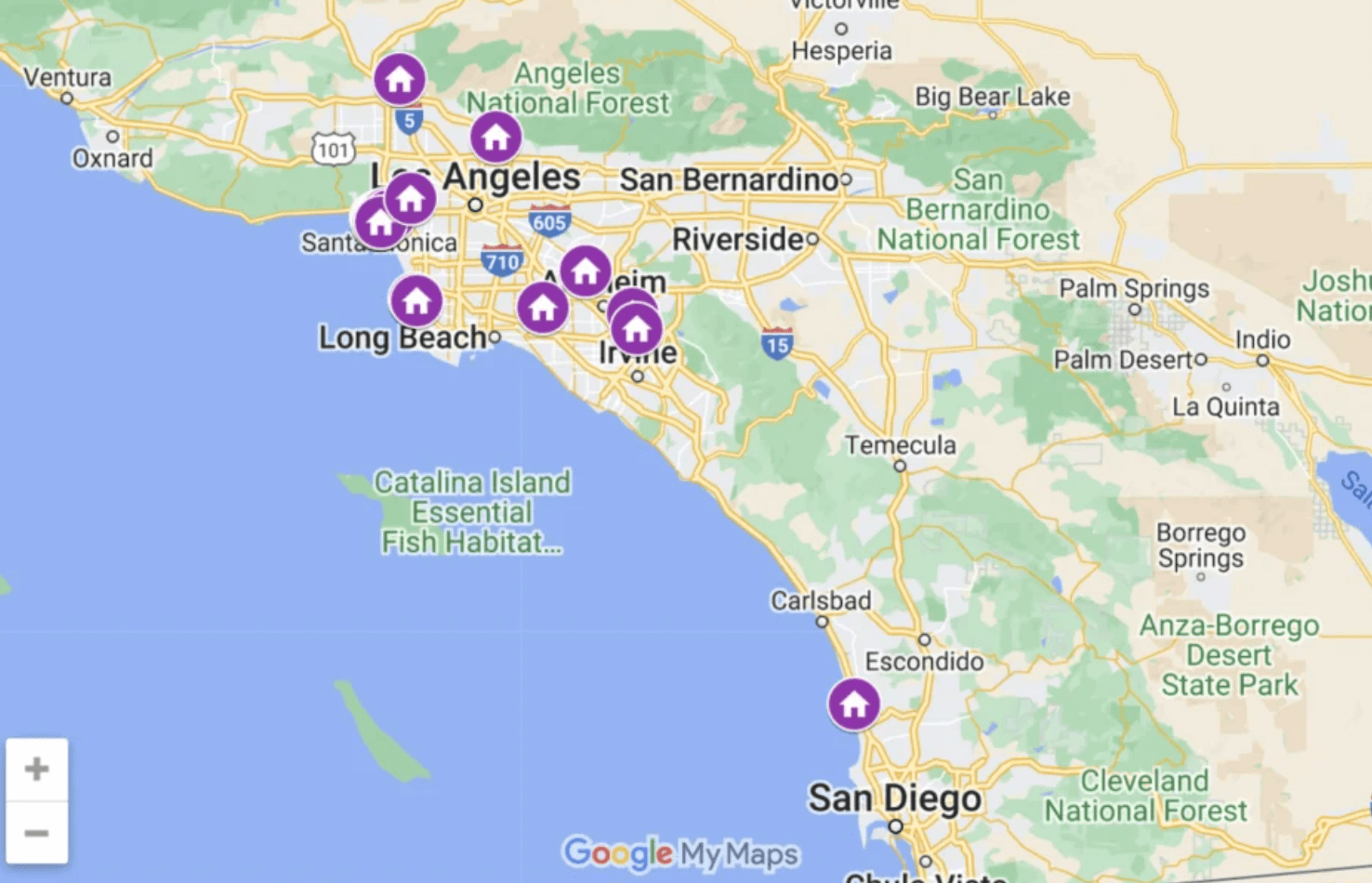

In Southern California, nine cities — from Del Mar to Sylmar — have received 26 builder’s remedy applications in the past eight months, seeking to build 8,642 new homes.

At least two or three Bay Area cities have received similar applications, according to press reports. The pro-housing group Yimby Law says developers are contemplating builder’s remedy applications in eight additional California cities.

And the potential for such projects is even higher — much higher. Almost half of California municipalities — including 116 in Southern California and 103 in the Bay Area — are vulnerable to the builder’s remedy because they don’t have a state-approved plan, known as a “housing element.”

Although the builder’s remedy has been on the books for three decades, it went virtually unused until last June.

So, why are developers rushing to take advantage of it now? And what, if anything, can municipalities without approved housing elements do to block them?

Anti-NIMBY act

The builder’s remedy was added to the state’s so-called “anti-NIMBY” Housing Accountability Act in 1990.

The measure sought “to force” reluctant communities into approving more low-income housing, the San Francisco Chronicle reported at the time.

Under this provision, cities and counties without a “substantially compliant” housing element can’t deny housing projects where 20% of the units are set aside for low-income residents or all of the units are affordable to moderate-income residents — even if they’re inconsistent with zoning rules or general plans.

“One might think developers in high-price places would be proposing massive condo projects hither and yon as soon as the deadline for housing element adoption passes,” UC Davis Law Professor Christopher Elmendorf, a housing element expert, tweeted in December 2021.

Southern California’s housing element deadline passed in 2021. The Bay Area’s deadline passed on Jan. 31.

Yet, Elemdorf could only find one use of the builder’s remedy prior to last year. In that case, a Bay Area homeowner sought to build a backyard unit without the two parking spaces the city required.

Why now?

In brief, Elmendorf said in an email, it’s gotten a lot harder for cities to adopt compliant housing elements because of increased homebuilding goals and because of greater requirements to address fair housing issues.

“There are a lot more places where (the builder’s remedy) applies,” said Sonja Trauss, YIMBY Law’s executive director. “This cycle, it’s a lot harder to get your housing element approved because the standards went up.”

The builder’s remedy gained added muscle from Senate Bill 330, a 2019 law allowing homebuilders to ”vest” their development rights by filing a bare-bones “preliminary application” for the builder’s remedy before a housing element gets approved.

“Developers who file an SB 330 application while a jurisdiction is out of compliance lock in their ability to use the builder’s remedy, even if the jurisdiction comes into compliance later,” said Ken Stahl, director of Chapman University’s Environmental, Land Use & Real Estate Law program. “Any subsequent changes to those standards cannot be applied to your project.”

‘Everyone’s worried’

Anxiety over the provision is growing, observers say.

“Listen to pretty much any Bay Area city council meeting about the housing element,” Elmendorf said. “Everyone’s worried about the builder’s remedy.”

“Local control is of concern to cities. They want to maintain that,” added Elaine Lister, Mission Viejo community development director. “So I would say, yes, it’s a concern.”

An artist’s rendering showing WS Communities’ proposed 15-story, 2,000-unit apartment complex planned for a 3.3-acre parcel off Olympic Boulevard. WS Communities filed 14 of the 16 builder’s remedy applications in Santa Monica, seeking to build 4,535 apartments in the beachside city. (Image courtesy of WS Communities)

The Huntington Beach City Council plans to consider an ordinance at its March 7 meeting to outlaw builder’s remedy applications in their city, arguing that as a charter city, it’s not subject to such laws.

Legal experts dispute Huntington Beach’s immunity claim, which was asserted unsuccessfully in previous lawsuits.

“They’d probably lose (in court),” Elmendorf said.

But the bottom line is Huntington Beach, which has yet to adopt a state-approved housing element, doesn’t want to leave itself exposed to builder’s remedy projects, Huntington Beach City Attorney Michael Gates said in an email.

“Allowing such permanent development projects to recklessly be built throughout the city because the city may not have (state) approval is unconscionable,” Gates said.

Being first

Housing developer Akhilesh Jha said he was extremely nervous last June when he filed a builder’s remedy application for 45 townhomes on a residential street in Sylmar that’s zoned for single-family homes.

He couldn’t find any similar applications on the books. But he read the law and believed he qualified for the builder’s remedy. His application landed at Los Angeles City Hall five days before the state certified the city’s housing element on June 29.

But Jha is an engineer, not an attorney.

“There’s always a possibility that you’re missing something, that you’re unaware of something,” Jha said.

Then, when news broke last fall that developers were using the very same provision to build more than 4,000 homes in Santa Monica, “that kind of gave me confirmation and relief that, yes, this will work,” Jha said.

Sometimes it takes somebody being the first, said Matthew Gelfand, legal counsel for Californians for Homeownership, which has sued 16 California cities over their housing elements. Then, you “get other folks to start deciding, ‘hey, I want to do this, too.’ ”

The One Redondo mixed-use development on the AES power plant site calls for more than 3-million square feet of residential, hotel, office and retail space. 458 units would be for lower-income residents, making the project eligible for the builder’s remedy, which sidesteps local zoning rules. (Rendering courtesy One Redondo)

Since Jha’s application was filed, Los Angeles developer Leo Pustilnikov filed builder’s remedy applications to build 2,320 units in two Redondo Beach developments, plus 200 more in a 16-story high-rise in Beverly Hills.

Applications for 22 other projects — ranging from a 13-unit apartment building in Hawaiian Gardens to 530 homes in La Habra — have been filed since last summer. One developer, Los Angeles-based WS Communities, accounted for 14 of Santa Monica’s 16 applications.

“I think a lot of developers are just starting to get wind of it,” said Scott Choppin, chief executive for Long Beach-based Urban Pacific Development Group, which is using the builder’s remedy for its Hawaiian Gardens project. “It’s got (developers’) attention, and they’re trying to find out how it works.”

Local options

In Santa Monica, builder’s remedy projects would boost the city’s housing supply by 4,619 units, or almost 9%. The city attorney thinks there are options for toning those projects down, councilmember Brock said.

Most legal experts believe cities have few options other than getting their housing elements certified.

But Elmendorf conceded there are some things cities can attempt. They can try to apply “development standards” that remain in the law, such as health and safety — provided they have written health and safety standards at the time an application is filed. Or they can delay projects using the California Environmental Quality Act, or CEQA, and hope they don’t get nailed for a bad-faith violation of the state’s “anti-NIMBY” law, he said.

“The builder’s remedy has many ambiguities,” Elmendorf said.

In addition, some cities may claim to have a “substantially compliant” housing element, even though the state hasn’t finished reviewing it.

“There was a lot of uncertainty regarding what it means for a housing element to be ‘substantially compliant,’ ” Chapman University’s Stahl said. “And there is some older case law holding that this is not a particularly high burden.”

Urban Pacific’s Choppin also worries that cities will “game the system endlessly” to frustrate developers pursuing the builder’s remedy.

“How much is the city going to mess with you on your plan check, on your inspections, (or say) you got to get the street repaved,” Choppin said. “The city (could) just punish you endlessly.”

For Jha, the Sylmar developer, obstacles to construction still loom. To his amazement, the city of Los Angeles maintains he still must go through the normal entitlement process and seek a zoning change and a general plan amendment for his 1.1-acre townhome project.

“The city is going to take you through a path that is windy,” Jha said. “They don’t want housing.”

Ultimately, the builder’s remedy could end up in court, said Stahl.

“There are some questions about the applicability of the builder’s remedy,” he said. “That may need to be ironed out in court, through clarifying legislation or administrative guidance from the (state).”